⛓️💥 Späti Stories #1: Meet Burkhart and Joachim - Tunnel Builders for Freedom

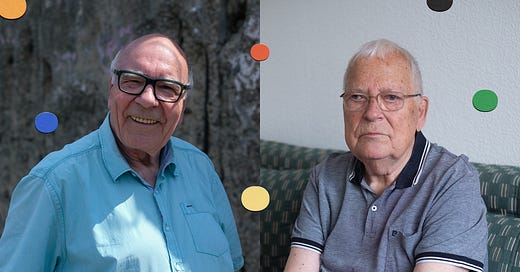

In this first issue, we honor Berlin's spirit of freedom with the stories of Burkhart Veigel and Joachim Neumann, two Berliners who risked their lives and defied the system for their community.

🎧 Listening to Heroes - David Bowie

“Two thousand years ago, the proudest boast was 'civis romanus sum' ['I am a Roman citizen']. Today, in the world of freedom, the proudest boast is 'Ich bin ein Berliner!'” declared U.S. President John F. Kennedy in 1963 at the Rathaus Schöneberg in West Berlin.

Since we moved to Berlin, if we had to describe the city in one word, it would be freedom—the freedom to dress, live, and be who you want to be. The city’s free spirit is deeply rooted in its history, marked by a long fight for liberation.

In honor of this spirit, we kick off Späti Stories with two interviews concerning freedom. In this first issue, you’ll read about Burkhart Veigel and Joachim Neumann, two Berliners who risked their lives to help their community and stand up to the system.

We launched Späti Stories to share the inspiring tales of people who make this city so unique. To do their stories justice, our first edition is longer than usual—but bear with us, we believe it’s worth your time.

They were heroes, not just for one day.

Burkhart Veigel is a doctor and music enthusiast born in Thüringen. He later moved to Tübingen, West Germany. He began building tunnels in 1961 while studying medicine in Berlin, helping people escape from East to West Berlin. By 1970, he had helped 950 people cross over — “from a dictatorship to their freedom,” as he describes it.

→ You were born in Thuringia but said you “became human” in Berlin. What makes you say that?

I played a lot of music, first the violin, then the viola. I was involved in several ensembles, including a sizeable 100-person orchestra. I studied anything that came my way—philosophy, law, sociology, journalism. Anything but medicine, as that was my main field of study. I kind of left that on the side because I had to do it anyway. And then I came to Berlin.

Art in Berlin was, of course, a big highlight, even in East Berlin. When the border was closed—I said to myself: “This can’t be real”. The students I knew, the so-called "border-crosser students" who had been studying with me at the Freie Universität, could no longer attend the university.

The border was closed on August 13th, but until August 22nd, 1961, West Berliners were still allowed to cross. During those nine days, about 6,100 people fled, and the GDR couldn’t handle it. So, they barred all West Berliners from crossing. Only West Germans and foreigners were allowed. Then my friend said, “you’ve got a West German ID card, you can still cross”. He asked me to help, and I immediately agreed. On the same day he approached me, I brought my first refugee to the West.

That is why I said I became human in Berlin.

→ What motivated you, as a West German man with no family on the other side, to risk your life helping others escape?

I didn’t have a very good childhood. My father was a pastor. He died in the war in 1942 when I was four years old. My mother wanted to make me a good Christian, which, of course, involved a lot of beatings and various other things.

I was often punished, locked up, and my desire for freedom kept growing. For me, freedom is more important than eating or drinking. It didn’t matter if someone in East Berlin was from my family—if they valued freedom, I was there to help.

→ Do you realize that what you did required a lot of bravery?

That never played a role. I think bravery isn’t about knowing you’re brave, it’s about doing what needs to be done. It wasn’t about whether it would cost me time, whether I’d lose years of study, or if it would cost me money. When I needed money, I did what was necessary. Whether I lost time, hurt my family, or anything else, it wasn’t something I thought about. You do what’s necessary without thinking about whether it’s brave or not.

But of course, it’s also an emotional question. It’s not purely intellectual, like "I’m doing this for a reason." I wasn’t fighting for freedom in that sense. What is freedom anyway? Freedom from, freedom for—I don’t know what freedom is, but I know what lack of freedom is, and I fought against that.

→After more than 30 years living and working as a doctor in Stuttgart, you came back to Berlin to help with research. How did you make that decision?

After more than 30 years, I met up again with my old escape helper friends for the first time. And it became clear to us that someone had to write things down. If it wasn’t written down, it would be lost. We met in 2001. I had planned to retire in 2006, and then I could work on the research.

Then I moved to Berlin and from that point on, I started doing interviews. I did about 100 interviews with refugees, escape helpers, and politicians—but mostly with refugees. I had to track them down because, of course, we hadn’t stayed in contact over the years.

My job was essentially to bring the experience back to life from history—not just files, but the people who fled back then or who helped others flee. That’s why I’ve also written a book titled Wege durch die Mauer: Fluchthilfe und Stasi zwischen Ost und West, in which I portray these people and try to recreate what life was like back then.

→ What defines Berlin for you? Can you share a memory that illustrates that?

I studied in Tübingen and Hamburg, and there it became clear to me: if you don’t belong, you’re an outsider. In Berlin, it was different. No matter where you came from, you belonged.

My first wife used to joke that she ended up with a Swabian of all people. But despite my Swabian accent, I was well-integrated in Berlin. In other cities, it’s often different. But in Berlin, I’ve always felt at home.

Coming from a small town, I remember a moment that impressed me: standing on the bridge over Gesundbrunnen a long time ago. I looked around and there was this six-lane road, and underneath it there were 20 train tracks. And every three minutes, a plane flew from Tempelhof. That was the dynamism I loved about this city.

I feel comfortable in Berlin. I don’t know everything, I’ve never been to Berghain or KitKat, but Berlin offers me so many opportunities that I feel like I’m missing out on something every day. But that’s okay because I can’t take in more than I already do.

Joachim Neumann was born in East Berlin and escaped to West Berlin in December 1961. As a civil engineering student, he quickly got involved in tunnel building, participating in the construction of six tunnels. His goal was to help his girlfriend, friends, and others escape.

→ You grew up in the GDR. What was East Berlin like?

When I was a child, in the late 1940s, both parts of the city had been completely destroyed by the war. There wasn’t much to eat, no luxuries, and we as children played in the ruins, which was strictly forbidden, but we did it anyway. When I became a teenager, in the 1950s, the two parts of Berlin started to diverge significantly. East Berlin was occupied by the Soviet Union, and the societal conditions were adjusted to those of the Soviet Union. That meant there was only one party in charge. The political pressure in schools and later at university was very strong.

They always explained to us that under socialism, workers would be better off, while under capitalism, it was the opposite—workers would have it worse and worse. My parents had many friends in West Berlin. We often visited them. These people were simple workers like my parents, but as a teenager, I noticed that in West Berlin, they had a washing machine, a fridge, a television—things we didn’t have. That’s when I began to have doubts about the things we were being taught in school, about the supposed advantages of socialism.

→ Did you always have the idea to flee at some point, or was there a decisive moment?

Something gave me a final push. A school friend of mine was sentenced to a long prison term for something he didn’t really do.

We were on vacation at the Baltic Sea, and he went to a nearby town because there was a festival happening. There was a big beer tent where people were drinking beer in the evening. A group of young people, whom he didn’t know, were sitting there listening to rock Western music. This was forbidden in the GDR. So, eventually, the owner of the tent called the police.

A truckload of riot police arrived, and they started grabbing people randomly, loading them onto the truck. It turned out that my friend was a student living in East Berlin, but he was studying in the West, since he couldn’t get a place to study in the GDR for political reasons, like many others.

They said, "This guy is the leader; he orchestrated all of this. He’s a provocateur sent from the West." And for that incident, even though he didn’t do anything except being there, he got sentenced to eight years in prison. It was an absolute shock for us. And that was the final straw - we decided to leave.

→ How did you start building tunnels after you escaped? What was your motivation?

Well, first of all, in East Berlin, there were six of us who were very good friends. And after what happened with our friend who ended up in prison, all six of us said, “We want out. We don’t want anything more to do with this state.” And we promised each other that whoever made it to West Berlin would try to help the others who were still in the East. Three of us, including me, made it to West Berlin. That was really the beginning—three of us wondering how we could help the others. And that’s when the idea of building a tunnel came up. It wasn’t as strange as it might sound today.

I also had a girlfriend who stayed in East Berlin. We tried to get her and my friends out through a tunnel, but the first attempt failed. Someone betrayed our group and ratted out the tunnel to the Stasi, and they were all arrested. My girlfriend was sentenced to 21 months in prison for “attempting to flee the republic,” as it was called back then. She was in prison, and I had no contact with her. But I continued building tunnels because I believed that she would be free eventually. I never gave up hope of getting her out.

At that time, a huge number of tunnels were being built. In the first four or five years after the wall went up, about 70 tunnel-building attempts were made, although, as far as I know, fewer than 20 were successful.

We met other guys in West Berlin in situations similar to ours. And so, we became a group of 7 or 8 people who seriously tried to build a tunnel. But it wasn’t easy. The first thing you needed was a starting point. That could only be a basement. We couldn’t just start digging out in the open; then, the whole city would have noticed.

It wasn’t easy to find something like that. From what I remember, finding a place took us two or three months. Then, through various connections, one of us heard that someone knew someone who was already building a tunnel. We teamed up and became a solid group of about 17 people.

→ Did your girlfriend leave prison and manage to escape?

Yes - she did - in the largest mass escape through a tunnel ever, where 57 people fled, in October 1964. At that time, my girlfriend should have had 5 more months in prison. On the day we planned to open the tunnel and bring the escapees through, I received a letter from her saying she had been released early.

Of course, I immediately tried to notify her, but that wasn't so easy. Informing the escapees could only be done through personal contact. This meant we always had to send couriers across. You couldn't write such sensitive information in a letter. So, we relied on couriers, usually West German or foreign students, who could travel to East Berlin freely and inform the would-be escapees of where and when to be, how to behave, and so on.

When I got her letter, all the couriers were already on their way to East Berlin. At the moment, there was no one left that we knew who could go over. Then I remembered that I was living in a shared flat with five other guys, and one of them had lived in a student dorm for a year before moving in with us. I confided in him and said, "Listen, there's a tunnel opening tonight, and my girlfriend, who was just released from prison, could come through, but I have no one to inform her. Could you go to your former dorm and see if you can find someone willing to do it?"

My friend said, "Sure, I'll try". Then he asked, "But if someone goes to see your girlfriend, how will she know he's coming really from you?". That was a good question, and then I came up with the idea: she had once gifted me a small teddy bear that became our mascot.

I gave it to him and said, "Whoever goes to inform her should take this teddy bear. When she sees it, she'll know that person can only come from me." It was a special teddy bear that had lost a leg, and she had sewn it back on. I told him, "She'll recognize it among 100 other teddy bears."

So, my friend took it, and I went to the tunnel to start the operation. The escapees came, but I didn't know if my friend had found someone to contact my girlfriend. She had just spent 16 months in prison for attempting to escape through a tunnel, and I wasn't entirely sure if the first thing she would do after being released was to try escaping again. But it all worked out - she escaped through the tunnel that night.

→ How was that moment when you both saw each other in the tunnel?

It was a very emotional moment. I was standing in a courtyard in East Berlin. There were four of us, and our job was to greet the escapees, guide them, and calm them down since they were all very nervous. It was dark, and one of my friends came across the courtyard with a young woman, holding her by the shoulder. He pushed her towards me and said, "Take care of her, she’s very nervous." When I took her to guide her down into the tunnel entrance, we recognized each other.

→ What main lesson has Berlin brought to you?

What I learned during the time after reunification is to be open to the world. Some people are surprised when you walk down the streets; it feels like every second person you meet is a foreigner. But I find that fascinating. And that extends to the culinary side, too. The variety of restaurants and food stalls from all over the world—it’s fantastic. You can taste the whole world right here in Berlin - and that comes with, of course, the culture of the foreign people as well. That amazes me.

We first came across Burkhart and Joachim’s incredible stories during a tour with Berliner Unterwelten, and they’ve stayed with us ever since. When Späti Stories was born, they were the first to come to mind. Berlin is full of inspiring, untold stories, and with this project, we aim to find—and share—them.

If you’ve read this far, it means these stories caught your attention just as they caught ours. If so, leave us a comment or share with friends who could use a dose of Berlin positivity.

Happy start of Autumn,

Isabelle and Lua

Very impressive! I live in Switzerland and love Berlin, but I don't know too much about its history. So it's all the more exciting to read such personal underground stories. Looking forward to reading more about soon!

I was born and raised in Berlin, and I have never personally spoken to anyone who helped people flee during that time. It's so cool that you did and shared this insight with us! I’m curious to hear more stories about people living in Berlin!