📑 Späti Stories #9: Meet Wolfgang and Omar - Bureaucracy, Belonging, and What Integration Really Means

We met Wolfgang, who's helped 1,000+ immigrants through bureaucracy and community karaoke, and Omar, who went from Syrian musician to developer in Germany—and learned belonging is more than paperwork.

🎧 Listening to Homesick - Kings of Convenience

As immigrants in Germany, the topic of integration hits close to home. Questions about visas, citizenship, bureaucracy, speaking German, or simply connecting with Germans are woven into our daily lives. We both speak German and have the legal right to live here permanently, but bureaucracy remains a challenge—often intimidating and contributing to the feeling that you might never truly learn to navigate Berlin's social systems. I still remember those early days when I felt incredibly grateful for any help, even something as simple as someone making a phone call on my behalf.

That's why when we heard about Wolfgang Jäger, we couldn't help but smile. We knew immediately we had to interview him: this 70-year-old dedicates his retirement to helping immigrants navigate bureaucracy, completely free of charge. Having worked at the Jobcenter and having been a job application trainer for its clients for years, Wolfgang now finds joy in helping young people integrate into German society.

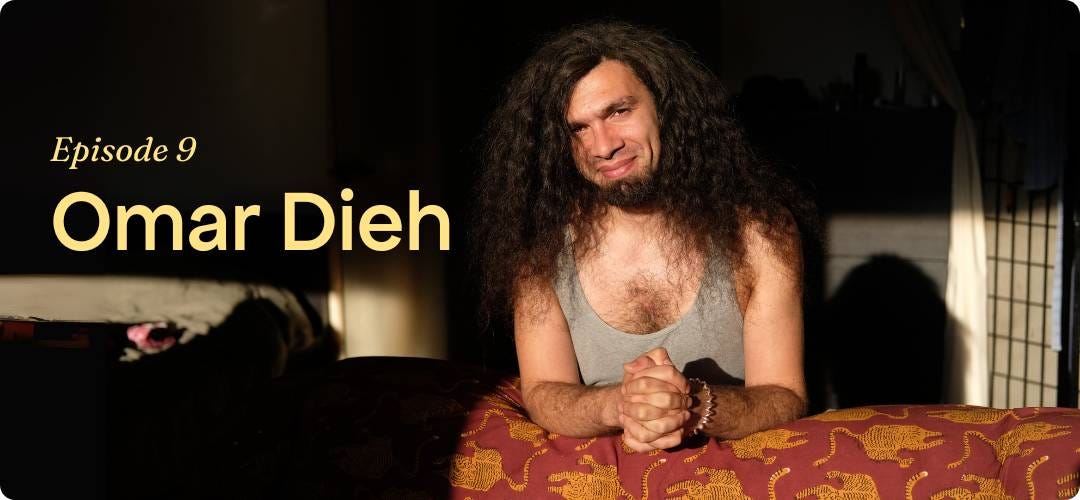

For this episode on integration, we also wanted to explore what "official integration" actually feels like. Does receiving German citizenship mark the end of the integration journey? We invited Omar Dieh, a musician and web developer who recently transitioned from refugee status to German citizenship, to share his personal journey with us.

We know our readers come from diverse backgrounds—some born German, others who emigrated here for countless different reasons. Given current world circumstances, we believe this topic resonates with many of you.

Grab your coffee, beer, water, or mate, and join us for this conversation.

Wolfgang Jäger, 70, was born in a village near Magdeburg and moved to East Berlin in his twenties. Twenty years ago, he began working for the JobCenter and later became a job application trainer. Now in retirement, he helps migrants navigate Berlin's bureaucracy free of charge and hosts monthly karaoke parties to connect the many young people he's helped along the way—probably over 1,000 by now.

We heard about Wolfgang through a friend who had attended his monthly karaoke party. "I've met so many interesting, different people," our friend Arjun shared, "including an Afghan musician couple who brought their violins and played for us." We were immediately intrigued by this mysterious and generous figure, and Arjun made the connection.

We scheduled the interview for last Thursday afternoon. He asked us to meet at his place, which also happens to be where he runs his volunteer operation. When we asked for the address, he sent us a pre-formatted message—an invitation to his monthly karaoke meeting with detailed directions to his flat. The polished format gave us the impression that these invitations go out to quite a long guest list.

We arrived at the location, about 15 minutes walking from Alexanderplatz, in one of those classic East Berlin heritage buildings. Immediately, we understood why the long explanation was necessary—the place looked like a labyrinth. It was also fascinating: vibrant colors, long corridors. We almost got lost but managed to find the flat with a golden nameplate reading "Jäger."

Wolfgang greeted us with a smile and a bright blue shirt that perfectly matched the summer vibe (and his sofa). His studio apartment with a separate kitchen was divided into distinct zones: his "office"—a couch with a table and all the gadgets necessary for his helping service; his bed area, where posters of The Beatles, a beach scene, and a newspaper article about his work hung on the wall; and a corner with a big TV, karaoke equipment, and an acoustic guitar. From the window, you could see and hear the tram and catch a clear view of the Fernsehturm.

After taking some portraits to make good use of the natural light, we sat down in his office corner. Though he speaks English quite well, we opted for German so he'd feel completely comfortable telling his story.

"I live here in Berlin, right in the center, and I'm very happy to be in this interesting place with so many opportunities," Wolfgang began when we asked how he'd introduce himself to a stranger. He explained that he helps young people navigate German bureaucracy—drawing on experience from his years working at the Jobcenter and later as a job application trainer. "I can help with applying for Bürgergeld, citizens' income, and other bureaucratic problems. Even some Germans find it difficult to understand."

Wolfgang's Berlin dream began early. "Ever since I was 13, I had the absolute wish to spend my life in Berlin." During a family vacation to East Berlin from his small village near Magdeburg, he fell in love with the capital. But under communist rule, life was controlled—where you could study, where you could work, where you could live after you finished a University study. After studying in Chemnitz and working in his home area, he finally transferred to Berlin at age 23. "I finally reached my goal, and I'm very happy about it. I think it was the best decision of my life."

Life in the GDR wasn't terrible for Wolfgang—he had family, work, and good friends. "Everyone worked—you had to work. There were no unemployed people, or hardly any." He earned good money and enjoyed life with his wife and friends, mostly avoiding political trouble. "I was against the government, against the communist regime, but I preferred to think about protecting my family." He knew opposition members who lost jobs or faced imprisonment. "We were young, we threw parties," he recalled, describing evenings in small pubs drinking beer together. But when the Wall fell, he was overjoyed. "I was really happy to realize how multicultural Berlin is. I liked that from the beginning—the multicultural side of it. I actively sought out contact in Kreuzberg with foreigners, just to learn more."

When the Wall fell, Wolfgang's world changed dramatically—starting with unemployment. His degree certificate literally read "socialist business administration," making him nearly unemployable in the new system. Rather than accept unemployment, he got a taxi license and drove for two to three years while building a new career. He transitioned into insurance sales, working primarily in former East Berlin where people needed new policies after the communist system dissolved.

During a brief unemployment period, he began helping others with Jobcenter forms—including foreigners he met while practicing his English. One day, he accompanied someone to a job application training course for their employment agency appointment. "I went to the course and told the instructor, 'I have to take him with me, he has an appointment at the employment agency.' And she said, 'Why are you taking him out of the course? What are you even doing here?' I said, 'I help people here,' and she asked, 'What kind of work have they done?' I told her. Then she said, 'You know what, we don't have a teacher for tomorrow. Do you have time to teach for us tomorrow?' And from that moment, I became a teacher. I filled in for a week, and then they said, 'This is working really well. We're hiring you.' So I became a job application training instructor. It was that simple, that quick."

Wolfgang's fascination with English started in high school and continued through self-study—listening to The Beatles and international radio like BBC and CNN. "I still have tons of vocabulary notebooks here. Whenever I come across a word, I write it down, and when I have time, I go to Friedrichshain park and review them."

His volunteer work grew naturally from his professional experience. As a trainer at a center in Kreuzberg, most of his students were foreigners. During breaks, students would approach him with forms they couldn't understand. "During breaks, they'd come up to me during class and ask, 'I have this form, how do I fill it out?'" He'd help them after class, sometimes visiting their homes or finding a quiet room at school.

After retirement, sitting at home felt wrong. "Just sitting at home wasting time in front of the TV, that's not a life," Wolfgang reflected. Many people he'd helped told him they would have returned to their home countries without his assistance—they simply had no chance of navigating the system alone.

Today, he helps over 100 people simultaneously with bureaucratic challenges. "It's not an exaggeration to say it's thousands" over the years, he explained. He meets most clients in person, accompanying them to appointments or inviting them to his home to fill out forms—though for first meetings, he often suggests meeting at a café instead.

He does all of this completely free of charge. After his ex-wife moved out, he rents two rooms in his apartment, which provides financial breathing room alongside his pension. "But actually, I don't need the money. I live a fairly modest life, but I can still afford things I want—like traveling." For him, the work itself is the reward.

The karaoke parties evolved organically from simple gatherings. "It was really nice to bring young people together, because in a way, they're all in the same boat." These connections lead to practical benefits—one young woman discovered a UX/UI design course through conversations at his party. "In the beginning, we didn't really do karaoke. We just played music here. People sang along, and then I thought, why not do this for real?"

For Wolfgang, the reward is emotional. "I really feel a lot when I can help. It makes me very happy when I see that people come out of difficult situations and suddenly find solutions." He paused, reflecting. "I have to say, I feel like I receive more than I give."

Berlin's multiculturalism delights him—something he's appreciated since reunification. "I'm glad that foreigners come here, that they're here, and that Berlin is this multicultural. It brings so many advantages for us Berliners."

However, he sees room for improvement in Germany's integration approach. Despite government talk of Willkommenskultur, he witnesses harsh treatment at government offices. "Government employees often refuse to speak English. Often they're just turned away harshly, especially if they can't speak German." He's even filed complaints about discriminatory behavior at various offices.

When we asked him to describe Berlin in one word, his answer came immediately: "Geil. Berlin ist geil."

💌 We're newsletter obsessed—that's why we started our own! Our monthly reads include: 20 Percent Berlin, Handpicked Berlin, From Julia’s Desk and The Next Day Berlin.

Omar Dieh, 35, based in Berlin, is a Syrian-born web developer and co-founder of Aleppo Shop. Before that, he had refugee status. But before that, he was a hip-hop musician in his home country. He recently received his German citizenship and now helps his sister with her shop, teaches people wanting to learn web development, all while continuing to make music as a hobby.

We also met Omar at his place for the interview. It was an incredibly sunny but windy day. At an intersection between Kreuzberg and Schöneberg, Omar's WG is definitely a unique flat—an Altbau of about 180 square meters with a living room ceiling that's a work of art in itself. He shares the space with three other people, each with a generously sized room plus a cozy but big communal living area. We could totally imagine all the parties hosted there.

Omar was immediately welcoming—hugging us, offering beers and snacks, making us feel completely comfortable. In typical Syrian hosting style, he insisted we settle in properly before we started the interview. We knew Omar had recently become German because he works with Lua—their colleagues had thrown a little celebration at the office.

His room was spacious, feeling like a small studio apartment divided into zones: a sleeping corner, a chill area with a couch, and a working corner with a desk, three screens, a cajón, and a guitar. From his desk, you could see his bike perched on top of the wardrobe.

"So, I did not really choose Berlin. Berlin chose me. And when we met, me and Berlin, it was love at first sight," Omar began. He explained that he's from Syria and left because of the war. "One of the options they gave me to be resettled in another country was Germany. It wasn't like a choice for us. They said, 'There is a possibility, we want you and your family to be resettled in Germany.' So it was good for us, but also our only option."

Omar comes from a place that, according to him, resembles Berlin in spirit. "Where I come from, a city called Aleppo, there is a neighborhood called Al-Aziziye. This neighborhood is like a small Berlin, where people come from all different neighborhoods and meet there to create. They do art, music, poetry, events. There are DJs, metal and rock bands, hip-hop, breakdance—you name it. That was the place where I felt like I belonged."

So in Al-Azizizye, in Aleppo, he felt at home. For the Syrian government and society, though, he was a rebel. He was arrested for promoting and playing music, accused of "disturbing the peace" and "promoting satanism." He was 17 years old.

The story of his arrest sounds almost surreal. Omar and two friends went to Damascus to hang concert posters—simple promotional material advertising their show. Around 9 or 10 PM, a civilian on a motorcycle stopped them, asked for their IDs, and told them to collect them the next day from the police office. "We went to the police station, and they said, 'Take the stairs down.' Once you know you're taking the stairs down with a police officer, that means you're going to the place where they put the jail. That's where the journey started."

He spent a month being transferred between different intelligence departments—seven days in each before being redirected. "We had a tour. It was a really nice non-musical tour to get to know our intelligence departments in Syria," he said sarcastically. Omar was 17, and during his department tour, he also spent 9 days in solitary confinement. He was laughing while he told us all that. We could see that this humor is part of his personality, but also his coping mechanism.

The situation was resolved around a month later, after he went to court. Because he was underage, Omar eventually had to appear before a civil judge rather than a military one. "This guy was reading our profile and laughing. He's like, 'What are you doing here? How?' And he said, 'Consider what happened with you a joke.' I'm like, 'Sure. It was super funny.'"

His first job in Berlin was whatever came his way—videography, camera work, audio mixing, mastering, recording. "I was just not really focused on doing anything specific, rather than just taking any opportunity," he explained.

Music is, according to him, "breathing with the heart." But he felt he couldn't do the same work he'd done in Syria, so he looked for something different but stable. "At some point I needed a type of job that is going to be stable, that is going to pay the bills at the end of the month. Music is a beautiful thing, but my mother tongue is Arabic. I speak English and a little German, but I never felt like I could perform music the same way in another language. And I'm not in my homeland. So I never thought of music to be the source where I feed myself here."

Since he already spent time on computers for video and audio editing, programming felt like something different that could give stability in this new reality. His motivation was also personal—he wanted to build a website and apps for his family's business. Today, his sister runs Aleppo Shop, an online store delivering over +1500 products to over 20 countries in Europe, which he helped build as co-founder.

Parallel to helping his sister with her e-commerce business, Omar also teaches web development at Ironhack to people wanting to learn—many of whom are looking to change careers. Change is a friend to Omar, so this made perfect sense to him.

He loves breaking down complex code that looks intimidating to beginners. "I enjoy having complicated stuff that people, when they look at it, they’re like, ‘What is this?’ And I’m like, ‘You think it looks like the Matrix? It’s actually something super simple once you understand it.’”. Omar finds joy in using real-life examples to make programming concepts accessible, watching students' faces light up when they overcome obstacles. "I enjoy when I see the face on people when they overcome an obstacle, and they feel relief. That motivates me".

Now that he has a full-time job that he enjoys, music has turned into his main hobby. He's had opportunities to play in Berlin in a band with his cousin—Ulaad Al Aam ("The Cousins" in Arabic)—but he prefers to keep music on the side. Both solo and with Ulaad Al Aam, he performed concerts around Berlin but didn't fully integrate into the German hip-hop scene, as the genre is deeply tied to language and culture. "It's more of a German language thing, and I come from a different hip-hop background. So I was more exposed in places where you would show multicultural music, rather than a specific genre."

After some years in Berlin, Omar and his whole family "became German." He was the last one to do it. "Now that you have German citizenship, do you feel integrated?" we asked him. Omar gazed at the window, where golden light shone through, and paused for a moment before answering."

”Nothing changed, to be honest, for me. The only thing that changed is that I now know I have the possibility to travel if I want to. I still didn't take advantage of that. I don't care about papers. I will belong once the people around me make me feel like I belong. Once I feel I have my Späti at the corner, and they recognize me, and I recognize them every day I pass by."

The topic of belonging seemed to resonate with Omar deeply. He paused, then continued: "I belong to the youth generation, to the young people who are open-minded, who understand that this world is beyond the boundaries their grandfathers built for them. If they have this understanding, then those are my people. I belong to so many friends here in Berlin who come from totally different parts of the world. But we share the same way of understanding what humanity means.”

A bit later, one of his best friends arrived—Lou-ay, also from Syria. Omar pointed at him, smiling, using him to illustrate what he had just said: that Lou-ay makes him feel at home, like he belongs.

Still on the integration topic, he told us that he's never experienced discrimination in Berlin related to his former refugee status, but that doesn't make him feel fully integrated either. "I had a really good experience with Berlin as a place that hosted me as a foreigner. Berliners are a different spirit than other Germans. They're more open for strangers. Plus, if you go on a bus in Berlin—out of ten people—there is only one Berliner. The rest are also coming from everywhere. So you don't feel like I'm the only stranger here. It does not really feel like home, but it's also not home for anyone else."

Omar has always disliked being labeled as a refugee—this wasn't something he chose; it just happened to him. He wants people to see him for the other parts of who he is—including as a musician. "I want people who are interested in hip-hop music or this type of art. I don't want people to come to see a refugee dancing on a stage."

Even though he didn't choose to be a refugee, and this status doesn't define him, the experience is still part of his journey—and it changed him. "Before I left Syria, I was a person that never lost their land. I remember the stability there. And then suddenly everything changed." The weight of that loss shaped his perspective in unexpected ways: "The experience of being a refugee definitely pushes your personality to become more humble—the way that you see the world, the way that you see your fellow human beings. Before being a refugee, in Syria, I had more pride. I had more arrogance."

What could help someone feel integrated, then? What could help Omar, beyond having his German papers, feel more at home? His answer was immediate: people could be warmer. "I'm grateful for the program that Germany gave me to get resettled, my family and I. But in general, I feel like people are cold. If it comes to emotions, to communication, to being warm with your neighbor. I don't really like not knowing the name of my neighbor. People here give each other too much space—to the extent where I wonder, 'Isn't this just loneliness?'"

Omar might not feel as at home as he did in Syria, but being in Berlin is now his new life, and we all have a favorite place in the city where we live. His? Schlachtensee. "It is where I reconnect with nature."

That surprised us—given his warmth and community focus, we expected his favorite place to be somewhere buzzing with people. But as you probably noticed from this reading, Omar is much more than just one thing, and choosing a peaceful lake as his sanctuary just reveals another layer of who he is.

Writing these two stories made us reflect on what it means to feel welcomed, or what it means to belong. Is speaking German enough? Will we finally feel fully German once we get our citizenship? Or is it going to happen when we feel empowered to tell people that they're separating their trash wrong?

We realized that each of these things, alone, won't do it. But as you gather more pieces of the puzzle together, it makes a difference. And feeling fluent in the bureaucracy, or having someone like Wolfgang guide you through it, definitely makes it easier, too. So once you get your Anmeldung, your German, and your people, you'll probably feel at least halfway there.

Immigrating is a human thing. There's beauty in finding a common language, a universal ground—as Omar said, he belongs to “the young people who are open-minded, who understand that this world is beyond the boundaries their grandfathers built for them”. And so do we.

Cheers from multicultural Berlin,

Isabelle and Lua